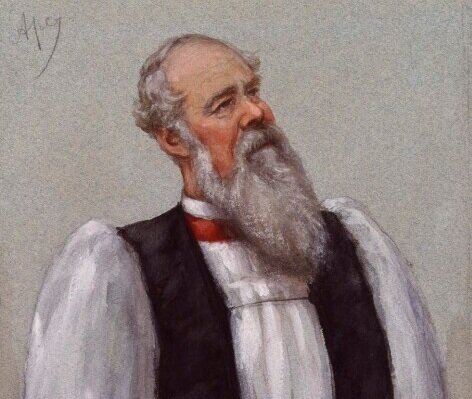

John Charles Ryle

John Charles Ryle (1816–1900) was educated at Christ Church, Oxford, where he was a Craven scholar. He was ordained in 1841 and became a leader of the evangelical party in the Church of England. In 1880, Ryle became the first Bishop of Liverpool and also served as the Dean of Salisbury. He remained the Bishop of Liverpool for 20 years. He was noted for his doctrinal essays and polemical writings.

Ryle wrote a series of essays which discuss nineteenth century doctrinal controversies from an evangelical viewpoint. The essay which follows is Ryle’s insightful comment on baptism in the post-Reformation English Church.

Knots Untied: PLAIN STATEMENTS ON DISPUTED POINTS IN RELIGION, FROM THE STANDPOINT OF AN EVANGELICAL CHURCHMAN.

BY THE LATE BISHOP JOHN CHARLES RYLE, D.D. Author of "Expository Thoughts on the Gospels,” etc.,

PEOPLE'S EDITION. (Second Impression of 10,000)

LONDON: CHAS. J. THYNNE, WYCLIFFE HOUSE, GREAT QUEEN STREET, KINGSWAY, W. C.

[1900AD edition]

CHAPTER V. BAPTISM

THERE is perhaps no subject in Christianity about which such difference of opinion exists as the sacrament of baptism. The very name recalls to one’s mind an endless list of strifes, disputes, heart-burnings, controversies, and divisions. It is a subject, moreover, on which even eminent Christians have long been greatly divided. Praying, Bible-reading, holy men, who can agree on all other points, find themselves hopelessly divided about baptism. The fall of man has affected the understanding as well as the will. Fallen indeed must human nature be, when millions who agree about sin, and Christ, and grace, are as the poles asunder about baptism. I propose in the following pages to offer a few remarks on this disputed subject. I am not vain enough to suppose that I can throw any light on a controversy which so many great and good men have handled in vain. But I know that every additional witness is useful in a disputed case. I wish to strengthen the hands of those I agree with, and to show them that we have no reason to be ashamed of our opinions. I wish to suggest a few things for the consideration of those I do not agree with, and to show them that the Scriptural argument in this matter is not, as some suppose, all on one side.

There are four points which I propose to examine in considering the subject:

What baptism is,—its nature.

In what manner baptism should be administered,—its mode.

Who ought to be baptized,—its subjects.

What place baptism ought to occupy in religion,—its true position.

If I can supply a satisfactory answer to these four questions, I feel that I shall have contributed something to the clearing of many minds.

Let us consider first the nature of baptism,—what is it?

Baptism is an ordinance appointed by our Lord Jesus Christ, for the continual admission of fresh members into His visible Church. In the army every new soldier is formally added to the muster-roll of his regiment. In a school every new scholar is formally entered on the books of the school. And every Christian begins his Church-membership by being baptized.1

Baptism is an ordinance of great simplicity. The outward part or sign is water, administered in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, or in the name of Christ. The inward part, or thing signified, is that washing in the blood of Christ, and inward cleansing of the heart by the Holy Ghost, without which no one can be saved. The Twenty-seventh Article of the Church of England says rightly,—“Baptism is not only a sign of profession and mark of difference, whereby Christian men are discerned from others that be not christened, but it is also a sign of regeneration or new birth.”

Baptism is an ordinance on which we may confidently expect the highest 2 blessings, when it is rightly used. It is unreasonable to suppose that the Lord Jesus, the Great Head of the Church, would solemnly appoint an ordinance which was to be as useless to the soul as a mere human enrolment or an act of civil registration. The sacrament we are considering is not a mere man-made appointment, but an institution appointed by the King of kings. When faith and prayer accompany baptism, and a diligent use of Scriptural means follows it, we are justified in looking for much spiritual blessing. Without faith and prayer baptism becomes a mere form.

Baptism is an ordinance which is expressly named in the New Testament about eighty times. Almost the last words of our Lord Jesus Christ were a command to baptize: “Go ye, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.” (Matt. xxviii. 19.) We find Peter saying on the day of Pentecost,—“Repent, and be baptized every one of you;”— and asking in the house of Cornelius,—“Can any man forbid water, that these should not be baptized?” (Acts ii. 38; x. 47.) We find St. Paul was not only baptized himself, but baptized disciples wherever he went. To say, as some do, in the face of these texts, that baptism is an institution of no importance, is to pour contempt on the Bible. To say, as others do, that baptism is only a thing of the heart, and not an outward ordinance at all, is to say that which seems flatly contradictory to the Bible.

Baptism is an ordinance which, according to Scripture, a man may receive, and yet get no good from it. Can anyone doubt that Judas Iscariot, Simon Magus, Ananias and Sapphira, Demas, Hymenaeus, Philetus, and Nicolas, were all baptized people? Yet what benefit did they receive from baptism? Clearly, for anything that we can see, none at all! Their hearts were “not right in the sight of God.” (Acts viii. 21.) They remained “dead in trespasses and sins,” and were “dead while they lived.” (Ephes. ii. 1; 1 Tim. v. 6.)

Baptism is an ordinance which in apostolic times went together with the first beginnings of a man’s religion. In the very day that many of the early Christians repented and believed, in that very day they were baptized. Baptism was the expression of their new-born faith, and the starting-point in their Christianity. No wonder that in such cases it was regarded as the vehicle of all spiritual blessings. The Scriptural expressions, “buried with Christ in baptism”— “putting on Christ in baptism”—“baptism doth also save us”—would be full of deep meaning to such persons. (Rom. vi. 4; Col. ii. 12; Gal. iii. 27; 1 Pet. iii. 21.) They would exactly tally with their experience. But to apply such expressions indiscriminately to the baptism of infants in our own day is, in my judgment, unreasonable and unfair. It is an application of Scripture which, I believe, was never intended.

Baptism is an ordinance which a man may never receive, and yet be a true Christian and be saved. The case of the penitent thief is sufficient to prove this. Here was a man who repented, believed, was converted, and gave evidence of true grace, if any one ever did. We read of no one else to whom such marvelous words were addressed as the famous sentence, “Today shalt thou be with Me in paradise.” (Luke xxiii. 42.) And yet there is not the slightest proof that this man was ever baptized at all! Without baptism and the Lord’s Supper he received the highest spiritual blessings while he lived, and was with Christ in paradise when he died! To assert, in the face of such a case, that baptism is absolutely necessary to salvation is something monstrous. To say that baptism is the only means of regeneration, and that all who die unbaptized are lost forever, is to say that which cannot be proved by Scripture, and is revolting to common sense.

I leave this part of my subject here. I commend the seven propositions which I have laid down to the serious attention of all who wish to obtain clear views about baptism. In considering the two sacraments of the Christian religion, I hold it to be of primary importance to put away from us the vagueness and mysteriousness with which too many surround them. Above all, let us be careful that we believe neither more nor less about them than we can prove by plain texts of Scripture.

There is a baptism which is absolutely necessary to salvation, beyond all question. There is a baptism without which no one, whether old or young, has over gone to heaven. But what baptism is this? It is not the baptism of water, but the inward baptism which the Holy Ghost gives to the heart. It is not a baptism which any man can offer, whether ordained or unordained. It is the baptism which it is the special privilege of the Lord Jesus Christ to give to all His mystical members. It is not a baptism which man’s eye can see, but an invisible operation on the inward nature. “Baptism,” says St. Peter, “saves us.” But what baptism does he tell us he means? Not the washing of water, “not the putting away the filth of the flesh.” (1 Peter iii. 21.) “By one spirit are we all baptized into one body?” (1 Cor. xii. 13.) It is the peculiar prerogative of the Lord Jesus to give this inward and spiritual baptism. “He it is,” said John the Baptist, “which baptizeth with the Holy Ghost.” (John I. 33.)

Let us take heed that we know something of this saving baptism, the inward baptism of the Holy Ghost. Without this it signifies little what we think about the baptism of water. No man, whether High Churchman or Low Churchman, Baptist or Episcopalian, no man was ever yet saved without the baptism of the Holy Ghost. It is a weighty and true saying of the Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge, in the reign of Edward VI.,—“By the baptism of water we are received into the outward Church of God: by the baptism of the Spirit into the inward.” (Bucer, on John I. 33.)

Let us now consider the mode of Baptism. In what way ought it to be administered?

This is a point on which a wide difference of opinion prevails. Some Christians maintain strongly that complete immersion in water is absolutely necessary and essential to make a valid baptism. They hold that no person is really baptized unless he is entirely “dipped,” and covered over with water. Others, on the contrary, maintain with equal decision that immersion is not necessary at all, and that sprinkling, or pouring a small quantity of water on the person baptized, fulfils all the requirements of Christ.

My own opinion is distinct and decided, that Scripture leaves the point an open question. I can find nothing in the Bible to warrant the assertion that either dipping, or pouring, or sprinkling, is essential to baptism. I believe it would be impossible to prove that either way of baptizing is exclusively right, or that either is downright wrong. So long as water is used in the name of the Trinity, the precise mode of administering the ordinance is left an open question.

This is the view adopted by the Church of England. The Baptismal Service expressly sanctions “dipping” in the most plain terms.3 To say, as many Baptists do, that the Church of England is opposed to baptism by immersion, is a melancholy proof of the ignorance in which many Dissenters live. Thousands, I am afraid, find fault with the Prayer-book without having ever examined its contents! If any one wishes to be baptized by “dipping” in the Church of England, let him understand that the parish clergyman is just as ready to dip him as the Baptist minister, and that he may be baptized by “immersion” in church as well as in chapel.

There is a large body of Christians, however, who are not satisfied with this moderate view of the question. They will have it that baptism by dipping or immersion is the only Scriptural baptism. They say that all the persons whose baptism we read of in the Bible were “dipped.” They hold, in short, that where there is no immersion there is no baptism.

I fear it is almost waste of time to attempt to say anything on this much disputed question. So much has been written on both sides without effect, during the last two hundred years that I cannot hope to throw any new light on the subject. The utmost that I shall try to do is to suggest a few considerations to any whose minds are in doubt. I only ask them to remember that I do not say that baptism by “dipping” is positively wrong. All I say is, that it is not absolutely necessary, and is not absolutely commanded in Scripture.

I ask, then, any doubting mind to consider whether it is in the least probable that all the cases of baptism described in Scripture were cases of complete immersion? The three thousand baptized in one day at the feast of Pentecost (Acts ii. 41),—the jailor at Philippi suddenly baptized at midnight in prison (Acts xvi. 33)—is it at all likely or probable that they were all “dipped”? To my own mind, trying to take an impartial view, it seems in the highest degree improbable. Let those believe it who can.

I ask anyone to consider, furthermore, whether it is at all probable that a mode of baptism would have been enjoined as necessary, which in some climates is impracticable? At the North and South Poles, for example, the temperature, for many months, is many degrees below freezing point. In tropical countries, on the other hand, water is often so extremely scarce that it is almost impossible to find enough for common drinking purposes. Now will any maintain that in such climates there can be no baptism without “immersion”? Will any one tell us that in such climates it is really necessary that every candidate for baptism should be completely dipped”? Let those believe it who can.

I ask anyone to consider, further, whether it is at all probable that a mode of baptism would have been enjoined which, in some conditions of health, is simply impossible. There are thousands of persons whose lungs and general constitution are in so delicate a state that total immersion in water, and especially in cold water, would be certain death to them. Now will any maintain that such persons ought to be debarred from baptism unless they are “dipped”? Let those believe it who can.

I ask anyone to consider, further, whether it is probable that a mode of baptizing would be enjoined, which in many countries would practically exclude women from baptism. The sensitiveness and strictness of Eastern nations about the treatment of their wives and daughters are notorious facts. There are many parts of the world in which women are so completely separated and secluded from the other sex, that there is the greatest difficulty in even speaking to them about religion. To talk of such an ordinance as baptizing them by “immersion” would, in hundreds of cases, be perfectly absurd. The feelings of fathers, husbands, and brothers, however personally disposed to Christian teaching, would be revolted by the mention of it. And will anyone maintain that such women are to be left unbaptized altogether because they cannot be “dipped”? Let those believe it who can.

I believe I might well leave the subject of the mode of baptism at this point. But there are two favourite arguments which the advocates of immersion are constantly bringing forward, about which I think it right to say something.

(a) One of these favourite arguments is based on the meaning of the Greek word in the New Testament, which we translate “to baptize.” It is constantly asserted that this word can mean nothing else but dipping, or complete “immersion.” The reply to this argument is short and simple. The assertion is utterly destitute of foundation. Those who are best acquainted with New Testament Greek are decidedly of opinion that to baptize means “to wash or cleanse with water,” but whether by immersion or not must be entirely decided by the context We read in St. Luke (xi. 38) that when our Lord dined with a certain Pharisee, “the Pharisee marveled that He had not first washed before dinner.” It may surprise some readers, perhaps, to hear that these words would have been rendered more literally, “that He had not first been baptized before dinner.”—Yet it is evident to common sense that the Pharisee could not have expected our Lord to immerse or dip Himself over head in water before dining! It simply means that he expected Him to perform some ablution, or to pour water over His hands, before the meal. But if this is so, what becomes of the argument that to baptize always means complete “immersion”? It is cut from under the feet of the advocate of “dipping,” and to reason further about it is mere waste of time.

(b) Another favourite argument in favour of baptism by immersion is drawn from the expression “buried with Christ in baptism,” which St. Paul uses on two occasions. (Rom. vi. 4; Col. ii. 12.) It is asserted that going down into the water of baptism, and being completely “dipped” under it, is an exact figure of Christ’s burial and coming up out of the grave, and represents our union with Christ and participation in all the benefits of His death and resurrection. But unfortunately for this argument there is no proof whatever that Christ’s burial was a going down into a hole dug in the ground. On the contrary, it is far more probable that His grave was a cave cut out of the side of a rock, like that of Lazarus, and on a level with the surrounding ground. Such, at least, was the common mode of burying round Jerusalem. At this rate there is no resemblance whatever between going down into a bath, or baptistry, and the burial of our Lord. The actions are not like one another. That by profession of a lively faith in Christ at baptism a believer declares his union with Christ, both in His death and resurrection, is undoubtedly true. But to say that in “going down into the water” he is burying his body just as His Master’s body was buried in the grave, is to say what cannot be proved.

In saying all this I should be very sorry to be mistaken. God forbid that I should wound the feelings of any brother who has conscientious scruples on this subject, and prefers baptism by dipping to baptism by sprinkling. I condemn him not. To his own Master he stands or falls. He that conscientiously prefers dipping may be dipped in the Church of England, and have all his children dipped if he pleases. What I contend for is liberty. I find no certain law laid down as to the mode in which baptism is to be administered, so long as water is used in the name of the Trinity. Let every man be persuaded in his own mind. He that sprinkles or simply pours water in baptism has no right to excommunicate him that dips;—and he that dips has no right to excommunicate him that sprinkles or pours water. Neither of them can possibly prove that the other is entirely wrong.

I leave this part of my subject here. Whatever some may think, I am content to regard the precise mode of baptizing as a thing indifferent, as a thing on which every one may use his liberty. I firmly believe that this liberty was intended of God. It is in keeping with many other things in the Christian dispensation. I find nothing precise laid down in the New Testament about ceremonies, or vestments, or liturgies, or church music, or the shape of churches, or the hours of service, or the quantity of bread and wine to be used at the Lord’s Supper, or the position and attitude of communicants. On all these points I see a liberal discretion allowed to the Church of Christ. So long as things are “done to edifying,” the principle of the New Testament is to allow a wide liberty.

I hold firmly, myself that the validity and benefit of baptism do not depend on the quantity of water employed, but on the state of heart in which the sacrament is used. Those who insist on every grown-up person being plunged over head in a baptistry, and those who insist on splashing an immense handful of water in the face of every tender infant they receive into the Church at the font, are both alike, in my judgment, greatly mistaken. Both are attaching far more importance to the quantity of water used than I can find warranted in Scripture. It has been well said by a great divine,—“A little drop of water may serve to seal the fullness of divine grace in baptizing as well as a small piece of bread and the least tasting of wine in the Holy Supper.” (Witsius, Econ. Fed. l. 4, ch. xvi. 30.) To that opinion I entirely subscribe.

Let us next consider the subjects of baptism. To whom ought baptism to be administered?

It is impossible to handle this branch of the question without coming into direct collision with the opinions of others. But I hope it is possible to handle it in a kindly and temperate spirit. At any rate it is no use to avoid discussion for fear of offending Baptists. Disputed points in theology are never likely to be settled unless men on both sides will say out plainly what they think, and give their reasons for their opinions. To avoid the subject, because it is a controversial one, is neither honest nor wise. A clergyman has no right to complain that his parishioners become Baptists, if he never instructs them about infant baptism.

I begin by laying it down as a point almost undisputed, that all grown-up converts at missionary stations among the heathen ought to be baptized. As soon as they embrace the Gospel and make a credible profession of repentance and faith in Christ, they ought at once to receive baptism. This is the doctrine and practice of Episcopal, Presbyterian, Wesleyan, and Independent missionaries, just as much as it is the doctrine of Baptists. Let there be no mistake on this point. To talk, as some Baptists do, of “believer’s baptism,” as if it was a kind of baptism peculiar to their own body, is simply nonsense! Believer’s baptism is known and practiced in every successful Protestant mission throughout the world.

But I now go a step further. I lay it down as a Christian truth that the children of all professing Christians have a right to baptism, if their parents require it, as well as their parents. Of course the children of professed unbelievers and heathen have no title to baptism, so long as they are under the charge of their parents. But the children of professing Christians are in an entirely different position. If their fathers and mothers offer them to be baptized, the Church ought to receive them in baptism, and has no right to refuse them.

It is precisely at this point that the grave division of opinion exists between the body of Christians called Baptists and the greater part of Christians throughout the world. The Baptist asserts that no one ought to be baptized who does not make a personal profession of repentance and faith, and that as children cannot do this they ought not to be baptized. I think that this assertion is not borne out by Scripture, and I shall proceed to give the reasons why I think so. I believe it can be shown that the children of professing Christians have a right to baptism, and that it is a complete mistake not to baptize them.

Let me remind the reader at the outset, that the question under consideration is not the Baptismal Service of the Church of England. Whether that service is right or wrong,—whether it is useful to have godfathers and godmothers,—are not the points in dispute. It is mere waste of time to say anything about them. 4 The question before us is simply whether infant baptism is right in principle. That it is right is held by Presbyterians, Independents, and Methodists, who use no Prayer-book, just as stoutly as it is by Churchmen. To the consideration of this one question I shall strictly confine myself. There is not the slightest necessary connection between the Liturgy and infant baptism. I heartily wish that some people would remember this. To insist on dragging in the Liturgy, and mixing it up with the abstract question of infant baptism, is not a sign of good logic, fairness, or common sense.

Let me clear the way, furthermore, by observing that I will not be drawn away from the real point at issue by the ludicrous descriptions which Baptists often give of the abuse of infant baptism. No doubt it is easy for popular writers and preachers among the Baptists, to draw a vivid picture of an ignorant, prayer-less couple of peasants, bringing an unconscious infant to be sprinkled at the font by a careless sporting parson! It is easy to finish off the picture by saying, “What good can infant baptism do?” Such pictures are very amusing, perhaps, but they are no argument against the principle of infant baptism. The abuse of a thing is no proof that it ought to be disused and is wrong. Moreover, those who live in glass-houses had better not throw stones. Strange pictures might be drawn of what happens sometimes in chapels at adult baptisms! But I forbear. I want the reader to look not at pictures but at Scriptural principles.

Let me now supply a few simple reasons why I hold, in common with all Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Independents throughout the world that infant baptism is a right thing, and that in denying baptism to children the Baptists are mistaken. The reasons are as follows.

(a) Children were admitted into the Old Testament Church by a formal ordinance, from the time of Abraham downwards. That ordinance was circumcision. It was an ordinance which God Himself appointed, and the neglect of which was denounced as a great sin. It was an ordinance about which the highest language is used in the New Testament. St. Paul calls it “a seal of the righteousness of faith.” (Rom. ii. 4.) Now, if children were considered to be capable of admission into the Church by an ordinance in the Old Testament, it is difficult to see why they cannot be admitted in the New. The general tendency of the Gospel is to increase men’s spiritual privileges and not to diminish them. Nothing, I believe, would astonish a Jewish convert so much as to tell him his children could not be baptized! “If they are fit to receive circumcision,” he would reply, “why are they not fit to receive baptism?” And my own firm conviction has long been that no Baptist could give him an answer. In fact I never heard of a converted Jew becoming a Baptist, and I never saw an argument against infant baptism that might not have been equally directed against infant circumcision. No man, I suppose, in his sober senses, would presume to say that infant circumcision was wrong.

(b) The baptism of children is nowhere forbidden in the New Testament. There is not a single text, from Matthew to Revelation, which either directly or indirectly hints that infants should not be baptized. Some, perhaps, may see little in this silence. To my mind it is a silence full of meaning and instruction. The first Christians, be it remembered, were many of them by birth Jews. They had been accustomed in the Jewish Church, before their conversion, to have their children admitted into church-membership by a solemn ordinance, as a matter of course. Without a distinct prohibition from our Lord Jesus Christ, they would naturally go on with the same system of proceeding, and bring their children to be baptized. But we find no such prohibition! That absence of a prohibition, to my mind, speaks volumes. It satisfies me that no change was intended by Christ about children. If He had intended a change He would have said something to teach it. But He says not a word! That very silence is, to my mind, a most powerful and convincing argument. As God commanded Old Testament children to be circumcised, so God intends New Testament children to be baptized.

(c) The baptism of households is specially mentioned in the New Testament. We read in the Acts that Lydia was baptized “and her household,” and that the jailer of Philippi “was baptized: he and all his.” (Acts xvi. 15, 33.) We read in the Epistle to the Corinthians that St. Paul baptized “the household of Stephanas.” (1 Cor. I. 16.) Now what meaning would any one attach to these expressions, if he had no theory to maintain, and could view them dispassionately? Would he not explain the “household” to include young as well as old, children as well as grown-up people? Who doubts when he reads the words of Joseph in Genesis, — “take food for the famine of your households” (Gen. Xlii. 33);—or, “take your father and your households and come unto me” (Gen. Xlv. 18), that children are included? Who can possibly deny that when God said to Noah, “Come thou and all thy house into the ark,” He meant Noah’s sons? (Gen. vii. 1.) For my own part I 9 cannot see how these questions can be answered without establishing the principle of infant baptism. Admitting most fully that it is not directly said that St. Paul baptized little children, it seems to my mind the highest probability that the “households” he baptized comprised children as well as grown-up people.

(d) The behaviour of our Lord Jesus Christ to little children, as recorded in the Gospels, is very peculiar and full of meaning. The well-known passage in St. Mark is an instance of what I mean. “They brought young children5 to Him, that He should touch them: and His disciples rebuked those that brought them. But when Jesus saw it, He was much displeased, and said unto them, Suffer the little children to come unto Me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God. Verily I say unto you, Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child, he shall not enter therein. And He took them up in His arms, put His hands upon them, and blessed them.” (Mark x. 13-16.)

Now I do not pretend for a moment to say that this passage is a direct proof of infant baptism. It is nothing of the kind. But I do say that it supplies a curious answer to some of the arguments in common use among those who object to infant baptism. That infants are capable of receiving some benefit from our Lord, that the conduct of those who would have kept them from Him was wrong in our Lord’s eyes, that He was ready and willing to bless them, even when they were too young to understand what He said or did,—all these things stand out as clearly as if written with a sunbeam! A direct argument in favour of infant baptism the passage certainly is not. But a stronger indirect testimony it seems to me impossible to conceive.

I might easily add to these arguments. I might strengthen the position I have taken up by several considerations which seem to me to deserve very serious attention. I might show, from the writings of old Dr. Lightfoot, that the baptism of little children was a practice with which the Jews were perfectly familiar. When proselytes were received into the Jewish Church by baptism, before our Lord Jesus Christ came, their infants were received, and baptized with them, as a matter of course.

I might show that infant baptism was uniformly practiced by all the early Christians. Every Christian writer of any repute during the first 1500 years after Christ, with the single exception of perhaps Tertullian, speaks of infant baptism as a custom which the Church has always maintained.

I might show that the vast majority of eminent Christians from the period of the Protestant Reformation down to the present day, have maintained the rights of infants to be baptized. Luther, Calvin, Melanchthon, and all the Continental Reformers,—Cranmer, Ridley, Latimer, and all the English Reformers,— the great body of all the English Puritans,—the whole of the Episcopal, Presbyterian, Independent, and Methodist Churches of the present day,—are all of one mind on this point. They all hold infant baptism!

But I will not weary the reader by going over this ground. I will proceed to notice two arguments which are commonly used against infant baptism, and are thought by some to be unanswerable. Whether they really are so I will leave the reader to judge.

The first favourite argument against infant baptism is the entire absence of any direct text or precept in its favour in the New Testament. “Show me a plain text,” says many a Baptist, “commanding me to baptize little children. Without a plain text the thing ought not to be done.” I reply, for one thing, that the absence of any text about infant baptism is, to my mind, one of the strongest evidences in its favour. That infants were formally admitted into the Church by an outward ordinance, for 1800 years before Christ came, is a fact that cannot be denied. Now, if he had meant to change the practice, and exclude infants from baptism, I should expect to find some plain text about it. But I find none, and therefore I conclude that there was to be no alteration and no change. The very absence of any direct command, on which the Baptists lay such stress, is, in reality, one of the strongest arguments against them! No change and therefore no text! But I reply, for another thing, that the absence of some plain text or command is not a sufficient argument against infant baptism. There are not a few things which can be proved and inferred from Scripture, though they are not plainly and directly taught. Let the Baptist show us a single plain text which directly warrants the admission of women to the Lord’s Supper.—Let him show us one which directly teaches the keeping of the Sabbath on the first day of the week instead of the seventh.—Let him show us one which directly forbids gambling. Any well instructed Baptist knows that it cannot be done. But surely, if this is the case, there is an end of this famous argument against infant baptism! It falls to the ground.

The second favourite argument against infant baptism is the inability of infants to repent and believe. “What can be more monstrous,” says many a Baptist, “than to administer an ordinance to an unconscious babe? It cannot possibly know anything of repentance and faith, and therefore it ought not to be baptized. The Scripture says, ‘He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved;’ and, ‘Repent, and be baptized.’” (Mark xvi. 16; Acts ii. 38.) In reply to this argument, I ask to be shown a single text which says that nobody ought to be baptized until he repents and believes. I shall ask in vain. The texts just quoted prove conclusively that grown-up people who repent and believe when missionaries preach the Gospel to them, ought at once to be baptized. But they do not prove that their children ought not to be baptized together with them, even though they are too young to believe. I find St. Paul baptized “the household of Stephanas “(1 Cor. I. 16); but I do not find a word about their believing at the time of their baptism. The truth is that the often-quoted texts, “He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved,”—and “Repent ye, and be baptized,” will never carry the weight that Baptists lay upon them. To assert that they forbid any one to be baptized unless he repents and believes, is to put a meaning on the words which they were never meant to bear. They leave the whole question of infants entirely out of sight. The text “nobody shall be baptized except he repents and believes,” would no doubt have been a very conclusive one. But such a text cannot be found! After all, will anyone tell us that an intelligent profession of repentance and faith is absolutely necessary to salvation? Would even the most rigid Baptist say that because infants cannot believe, all infants must be damned? Yet our Lord said plainly, “He that believeth not shall be damned.” (Mark xvi. 16.)—Will any man pretend to say that infants cannot receive grace and the Holy Ghost? John the Baptist, we know, was filled with the Holy Ghost from his mother’s womb. (Luke I. 15.)—Will anyone dare to tell us that infants cannot be elect,—cannot be in the covenant,—cannot be members of Christ,—cannot be children of God,—cannot have new hearts,—cannot be born again,—cannot go to heaven when they die?— These are solemn and serious questions. I cannot believe that any well-informed Baptist would give them any but one answer. Yet surely those who may be members of the glorious Church above, may be admitted to the Church below! Those who are washed with the blood of Christ, may surely be washed with the water of baptism! Those who can be capable of being baptized with the Holy Ghost, may surely be baptized with water! Let these things be calmly weighed. I have seen many arguments against infant baptism, which, traced to their logical conclusion, are arguments against infant salvation, and condemn all infants to eternal ruin!

I leave this part of my subject here. I am almost ashamed of having said so much about it. But the times in which we live are my plea and justification. I do not write so much to convince Baptists, as to establish and confirm Churchmen. I have often been surprised to see how ignorant some Churchmen are of the grounds on which infant baptism may be defended. If I have done anything to show Churchmen the strength of their own position, I feel that I shall not have written in vain.

Let us now consider, in the last place, what position baptism ought to hold in our religion.

This is a point of great importance. In matters of opinion man is ever liable to go into extremes. In nothing does this tendency appear so strongly as in the matter of religion. In no part of religion is man in so much danger of erring, either on the right hand or the left, as about the sacraments. In order to arrive at a settled judgment about baptism, we must beware both of the error of defect, and of the error of excess.

We must beware, for one thing, of despising baptism. This is the error of defect. Many in the present day seem to regard it with perfect indifference. They pass it by, and give it no place or position in their religion. Because, in many cases, it seems to confer no benefit, they appear to jump to the conclusion that it can confer none. They care nothing if baptism is never named in the sermon. They dislike to have it publicly administered in the congregation. In short, they seem to regard the whole subject of baptism as a troublesome question, which they are determined to let alone. They are neither satisfied with it, nor without it.

Now, I only ask such persons to consider gravely, whether their attitude of mind is justified by Scripture. Let them remember our Lord’s distinct and precise command to “baptize,” when He left His disciples alone in the world. Let them remember the invariable practice of the Apostles, wherever they went preaching the Gospel. Let them mark the language used about baptism in several places in the Epistles. Now, is it likely,—is it probable,—is it agreeable to reason and common sense,—that baptism can be safely regarded as a dropped subject, and quietly laid on the shelf? Surely, I think these questions can only receive one answer.

It is simply unreasonable to suppose that the Great Head of the Church would burden His people in all ages with an empty, powerless, unprofitable institution. It is ridiculous to suppose His Apostles would speak as they do about baptism, if, in no case, and under no circumstances, could it be of any use or help to man’s soul. Let these things be calmly weighed. Let us take heed, lest in fleeing from blind superstition, we are found equally blind in another way, and pour contempt on an appointment of Christ.

We must beware, for another thing, of making an idol of baptism. This is the error of excess. Many in the present day exalt baptism to a position which nothing in Scripture can possibly justify. If they hold infant baptism, they will tell you that the grace of the Holy Ghost invariably accompanies the administration of the ordinance,—that in every case, a seed of Divine life is implanted in the heart, to which all subsequent religious movement must be traced,—and that all baptized children are, as a matter of course, born again, and made partakers of the Holy Ghost!—If they do not hold infant baptism, they will tell you that to go down into the water with a profession of faith and repentance is the very turning-point in a man’s religion,—that until we have gone down into the water we are nothing,— and that when we have gone down into the water, we have taken the first step toward heaven! It is notorious that many High Churchmen and Baptists hold these opinions, though not all. And I say that although they may not mean it, they are practically making an idol of baptism.

I ask all persons who hold these exceedingly high and lofty views of baptism, to consider seriously what warrant they have in the Bible for their opinions. To quote texts in which the greatest privileges and blessings are connected with baptism, is not enough. What we want are plain texts which show that these blessings and privileges are always and invariably conferred. The question to he settled is not whether a child may be born again and receive grace in baptism, but whether all children are born again, and receive grace when they are baptized.—The question is not whether an adult may “put on Christ” when he goes down into the water, but whether all do as a matter of course. Surely these things demand grave and calm consideration!—It is positively wearisome to read the sweeping and illogical assertions which are often made upon this subject. To tell us, for example, that our Lord’s famous words to Nicodemus (John iii. 5), teach anything more than the general necessity of being “born of water and the spirit,” is an insult to common sense. Whether all persons baptized are “born of water and the Spirit” is another question altogether, and one which the text never touches at all. To assert that it is taught in the text, is just as illogical as the common assertion of the Baptist, when he tells you that because Jesus said, “He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved,”—therefore nobody ought to be baptized until he believes!

The right position of baptism can only be decided by a careful observation of the language of Scripture about it. Let a man read the New Testament honestly and impartially for himself. Let him come to the reading of it with an unprejudiced, fair, and unbiased mind. Let him not bring with him pre-conceived ideas, and a blind reverence for the opinion of any uninspired writing, of any man, or of any set of men. Let him simply ask the question,—“What does Scripture teach about baptism, and its place in Christian theology?”—and I have little doubt as to the conclusion he will come to. He will neither trample baptism under his feet, nor exalt it over his head.

(a) He will find that baptism is frequently mentioned, and yet not so frequently as to lead us to think that it is the very first, chief, and foremost thing in Christianity. In fourteen out of twenty-one Epistles, baptism is not even named. In five out of the remaining seven, it is only mentioned once. In one of the remaining two, it is only mentioned twice. In the two pastoral Epistles to Timothy it is not mentioned at all. There is, in short, only one Epistle, viz., the first to the Corinthians, in which baptism is even named on more than two occasions. And, singularly enough, this is the very Epistle in which St. Paul says, “I thank God that I baptized none of you,”—and “Christ sent me not be baptize, but to preach the Gospel.” (1 Cor. I. 14, 17.)

(b) He will find that baptism is spoken of with deep reverence, and in close connection with the highest privileges and blessings. Baptized people are said to be “buried with Christ,”—to have “put on Christ,”—to have “risen again,”—and even (by straining a doubtful text) to have the “washing of regeneration.” But he will also find that Judas Iscariot, Ananias and Sapphira, Simon Magus, and others, were baptized, and yet gave no evidence of having been born again. He will also see that in the first Epistle of John, people “born of God” are said to have certain marks and characteristics which myriads of baptized persons never possess at any period of their lives. (1 John ii. 29; iii. 9; v. 1, 4, 18.) And not least, he will find St. Peter declaring that the baptism which saves is “not the putting away the filth of the flesh,” the mere washing of the body, but the ‘“answer of a good conscience.” (1 Peter iii. 21.)

(c) Finally, he will discover that while baptism is frequently spoken of in the New Testament, there are other subjects which are spoken of much more frequently. Faith, hope, charity, God’s grace, Christ’s offices, the work of the Holy Ghost, redemption, justification, the nature of Christian holiness,—all these are points about which he will find far more than about baptism. Above all, he will find, if he marks the language of Scripture about the Old Testament sacrament of circumcision, that the value of God’s ordinances depends entirely on the spirit in which they are received, and the heart of the receiver. “In Jesus Christ neither circumcision availeth anything, nor uncircumcision; but faith which worketh by love,—but a new creature.” (Gal. v. 6; vi. 15.) “He is not a Jew which is one outwardly; neither is that circumcision which is out-ward in the flesh: but he is a Jew which is one inwardly; and circumcision is that of the heart, in the spirit, and not in the letter; whose praise is not of men, but of God.” (Rom. ii. 28, 29.) It only remains for me now to say a few words by way of practical conclusion to the whole paper. The nature, manner, subjects, and position of baptism have been severally considered.

Let me now show the reader the special lessons to which I think attention ought to be directed.

For one thing, I wish to urge on all who study the much-disputed subject of baptism, the importance of aiming at simple views of this sacrament. The dim, hazy, swelling words, which are often used by writers about baptism, have been fruitful sources of strange and unscriptural views of the ordinance. Poets, and hymn-composers, and Romish theologians, have flooded the world with so much high-flown and rhapsodical language on the point, that the minds of many have been thoroughly swamped and confounded. Thousands have imbibed notions about baptism from poetry, without knowing it, for which they can show no warrant in God’s Word. Milton’s Paradise Lost is the sole parent of many a current view of Satan’s agency; and uninspired poetry is the sole parent of many a man’s views of baptism in the present day. Once for all, let me entreat every reader of this paper to hold no doctrine about baptism which is not plainly taught in God’s Word. Let him beware of maintaining any theory, however plausible, which cannot be supported by Scripture. In religion, it matters nothing who says a thing, or how beautifully he says it. The only question we ought to ask is this,—“Is it written in the Bible? what saith the Lord?”

For another thing, I wish to urge on many of my fellow Churchmen the dangerous tendency of extravagantly high views of the efficacy of baptism. I have no wish to conceal my meaning. I refer to those Churchmen who maintain that grace invariably accompanies baptism, and that all baptized infants are in baptism born again. I ask such persons, in all courtesy and brotherly kindness, to consider seriously the dangerous tendency of their views, and the consequences which logically result from them. They seem to me, and to many others, to degrade a holy ordinance appointed by Christ into a mere charm, which is to act mechanically, like a medicine acting on the body, without any movement of a man’s heart or soul. Surely this is dangerous! They encourage the notion that it matters nothing in what manner of spirit people bring their children to be baptized. It signifies nothing whether they come with faith, and prayer, and solemn feelings, or whether they come careless, prayer less, godless, and ignorant as heathens! The effect, we are told, is always the same in all cases! In all cases, we are told, the infant is born again the moment it is baptized, although it has no right to baptism at all, except as the child of Christian parents. Surely this is dangerous! They help forward the perilous and soul-ruining delusion that a man may have grace in his heart, while it cannot be seen in his life. Multitudes of our worshippers have not a spark of religious life or grace about them. And yet we are told that they must all be addressed as regenerate, or possessors of grace, because they have been baptized! Surely this is dangerous! Now I firmly believe that hundreds of excellent Churchmen have never fully considered the points which I have just brought forward. I ask them to do so. For the honour of the Holy Ghost, for the honour of Christ’s holy sacraments, I invite them to consider seriously the tendency of their views. Sure am I that there is only one safe ground to take up in stating the effects of baptism, and that is the old ground stated by our Load: “Every tree is known by his own fruit.” (Luke vi. 44.) When baptism is used profanely and carelessly, we have no right to expect a blessing to follow it, any more than we expect it for a careless recipient of the Lord’s Supper. When no grace can be seen in a man’s life, we have no right to say that he is regenerate and received grace in baptism.

For another thing, I wish to urge on all Baptists who may happen to read this paper, the duty of moderation in stating their views of baptism, and of those who disagree with them. I say this with sorrow. I respect many members of the Baptist community, and I believe they are men and women whom I shall meet in heaven. But when I mark the extravagantly violent language which some Baptists use against infant baptism, I cannot help feeling that they may be justly requested to judge more moderately of those with whom they disagree. Does the Baptist mean to say that his peculiar views of baptism are needful to salvation, and that nobody will be saved who holds that infants ought to be baptized? I cannot think that any intelligent Baptist in his senses would assert this. At this rate he would shut out of heaven the whole Church of England, all the Methodists, all the Presbyterians, and all the Independents! At this rate, Cranmer, Ridley, Latimer, Luther, Calvin, Knox, Baxter, Owen, Wesley, Whitfield, and Chalmers, are all lost! They all firmly maintained infant baptism, and therefore they are all in hell! I cannot believe that any Baptist would say anything so monstrous and absurd. Does the Baptist mean to say that his peculiar views of baptism are necessary to a high degree of grace and holiness? Will he undertake to assert that Baptists have always been the most eminent Christians in the world, and are so at this day? If he does make this assertion, he may be fairly asked to give some proof of it. But he cannot do so. He may show us, no doubt, many Baptists who are excellent Christians. But he will find it hard to prove that they are one bit better than some of the Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Independents, and Methodists, who all hold that infants ought to be baptized. Now, surely, if the peculiar opinions of the Baptists are neither necessary to salvation nor to eminent holiness, we may fairly ask Baptists to be moderate in their language about those who disagree with them. Let them, by all means, maintain their own peculiar views, if they think they have discovered a “more excellent way.” Let them use their liberty and be fully persuaded in their own minds. The narrow way to heaven is wide enough for believers of every name and denomination. But for the sake of peace and charity, let me entreat Baptists to exercise moderation in their judgment of others.

In the last place, I wish to urge on all Christians the immense importance of giving to each part of Christianity its proper proportion and value, but nothing more. Let us beware of wresting things from their right places, and putting that which is second first, and that which is first second. Let us give all due honour to baptism and the Lord’s Supper, as sacraments ordained by Christ Himself. But let us never forget that, like every outward ordinance, their benefit depends entirely on the manner in which they are received. Above all, let us never forget that while a man may be baptized, like Judas, and yet never be saved, so also a man may never be baptized, like the penitent thief, and yet may be saved.—The things needful to salvation are an interest in Christ’s atoning blood, and the presence of the Holy Ghost in the heart and life. He that is wrong on these two points will get no benefit from his baptism, whether he is baptized as an infant or grown up. He will find at the last day that he is wrong for evermore.

FOOTNOTES

This is a point which ought to be carefully noticed. Here lies the one simple reason why the children of Baptists, or any other unbaptized persons, cannot have the Burial Service of the Prayer-book read over them, when they are buried. It is a service expressly intended for members of the professing Church. An unbaptized person is not such a member. There is, therefore, no Service that we can read. To suppose that we pronounce any opinion on a man’s state of soul and consider him lost, because we read no Service over him, is simply absurd! We pronounce no opinion at all. He may be in paradise with the penitent thief for anything we know. His soul after death is not affected either by reading a Service or by not reading one. The plain reason is we have nothing to read!

I am quite aware that the whole body of Christians called Friends, or Quakers, reject water baptism, and allow of no baptism except the inward baptism of the heart. To their own Master they must stand or fall. I am not their Judge. The grace, faith, and holiness of many Quakers are beyond all question. They are simple matters of fact. Christians like Mrs. Fry and J. J. Gurney most evidently had received the Holy Ghost, and would reflect honour on any Church. Would God that many baptized Christians were like them! But the best people are fallible at their best. How people, so sensible and well-read as many Quakers have been and are, can possibly refuse to see water-baptism to Scripture, as an ordinance obligatory on all professing Christians, is a problem which I cannot pretend to solve. It passes my understanding. I can only suppose that God allows the Quakers to be a perpetual testimony against Romish views of water-baptism, and a standing witness to the Churches that God can, in some cases, give grace without the use of any sacraments at all!

The rubric of the Prayer-book Service for the Public Baptism of Infants says,—“If the godfather and godmother shall certify to the priest that the child may well endure it, he shall dip it in the water discreetly and warily.”

Readers who wish to examine the true meaning of the Baptismal Service are requested to read the paper in this volume, called “Prayer-book Statements about Regeneration.”

In the parallel passage in St. Luke’s Gospel the word “infants” is used, and the Greek word so rendered can only be used of infants too young to speak or be called intelligent.